This is part 3 of a series in which I will show some of my approaches to a “Cloud Ready” web application with Clojure. If you are new to web apps with Clojure, you should read the first two parts, Cloudready Clojure Part 1 and Cloudready Clojure Part 2 first, where we set up a webserver, the base for serverside HTML rendering and a configuration mechanism which will work with cloud providers.

Cloud Ready Web Sessions

In the last blog post we realized that our handling of web sessions was not ideal if we wanted to run our application in the cloud. The session was stored in the memory, and would not support a setup with multiple nodes, let alone a setup with autoscaling nodes. There are two ways to work around this issue:

- Store the complete, encrypted session with all its data in a cookie, which is then sent from the users browser with every request.

- Store the session data in a database, which is accessed by all nodes of the application.

Storing the session in a cookie

For the first approach we don’t need an additional library. Ring supports two sessions store mechanisms out of the box, the memory-store (default) and cookie-store. If we wanted to store the session data in a cookie, we would add the cookie-store reference to our namespace, first, [ring.middleware.session.cookie :refer [cookie-store]]. Then we would add the cookie store to our site-defaults configuration, configured with a secret to encrypt the cookie data. As our main method fills up a little more now, we take some time to organize it with a let call:

(defn -main

"Starts the web server and the application"

[& args]

(let [cookiestore (cookie-store {:key "q3t6v9y$B&E)H@Mc"})

port (:port env)]

(run-jetty

(wrap-defaults app-handler (-> site-defaults

(assoc-in [:session :store] cookiestore)))

{:port port})))

After restarting the application, we can observe the changes in our cookie. The application would now be ready to be scaled horizontally, without worrying which request will go to which instance.

Storing the session in a database

I am not a huge fan of storing sensitive information on the user side, even if it is encrypted. I am also not a fan of big cookies which get sent around with every call, so I don’t tend to use the cookie store in my application. Storing the session in the database seems like a more sensible approach to me.

First we will need a database to store our session in. My default choice is PostgreSQL, but this will work with a lot of different databases, too. The quickest way to set up a local database is to use Docker. With the following command, our DB is up and ready to use:

docker run -p 5432:5432 --name scrapbook_db -e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=scrapsafe -d postgres:12.2

In order to connect to the database, we will add the dependency to the PostgreSQL JDBC driver to our build.boot file. And luckily we don’t need to store the session in the database all by ourselves - we can make use of the jdbc-ring-session library from the luminus-framework, which we will also include:

(set-env! :resource-paths #{"resources" "src"}

:source-paths #{"test"}

:dependencies '[[org.clojure/clojure "1.10.0"]

[adzerk/boot-test "1.2.0" :scope "test"]

[ring "1.8.0"]

[rum "0.11.4"]

[yogthos/config "1.1.7"]

[ring/ring-defaults "0.3.2"]

[org.postgresql/postgresql "42.2.11"]

[jdbc-ring-session "1.3"]])

Preparing and connecting to the database

jdbc-ring-session expects that we set up the table to store the data in. The DDL script can be looked up in their documentation, for PostgreSQL it looks like this:

CREATE TABLE session_store

(

session_id VARCHAR(36) NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

idle_timeout BIGINT,

absolute_timeout BIGINT,

value BYTEA

)

Now we can start replacing our cookie store with the jdbc store, which changes our ns header:

(ns scrapbook.core

(:require [ring.adapter.jetty :refer [run-jetty]]

[rum.core :refer [defc render-static-markup]]

[config.core :refer [env]]

[ring.middleware.defaults :refer [wrap-defaults site-defaults]]

[jdbc-ring-session.core :refer [jdbc-store]])

(:gen-class))

We proceed with providing the database connection details. We should not do this in the Clojure code, because this would make it hard for us to provide different configurations for different environments. As we did with the port of our HTTP Server earlier, we add the properties to our config.edn file:

{:port 80

:db {:subprotocol "postgresql"

:subname "postgres"

:user "postgres"

:password "scrapsafe"}}

The structure behind the :db keyword is already in the exact format which our session store expects, we can pass it directly into the store configuration, without any changes. We need to change our -main method to match the following code:

(defn -main

"Starts the web server and the application"

[& args]

(let [session-store (jdbc-store (:db env))

port (:port env)]

(run-jetty

(wrap-defaults app-handler (-> site-defaults

(assoc-in [:session :store] session-store)))

{:port port})))

Managing Session timeout

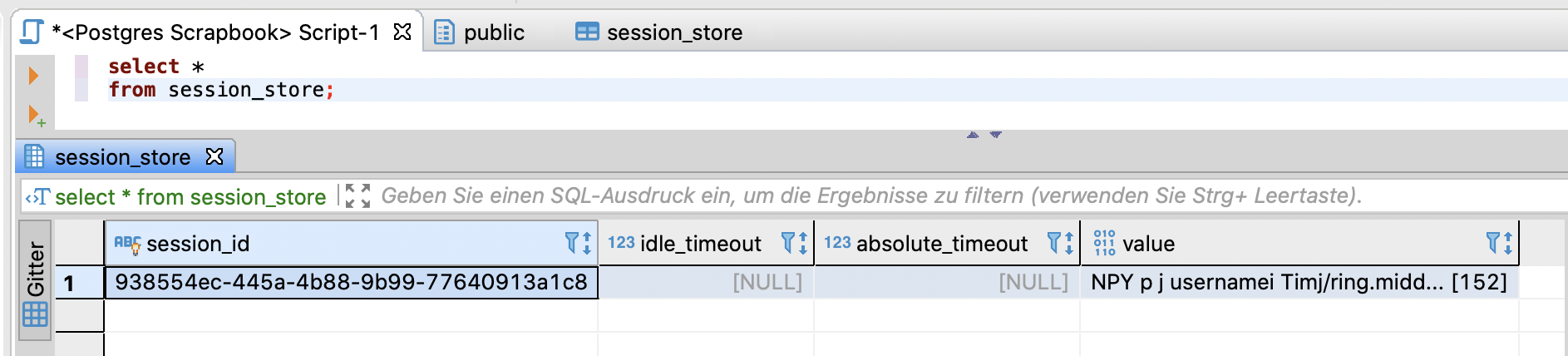

If we start the application again, with our already well known boot run command, it should start up without any errors. Using a DB management tool (e.g. DBeaver), we can inspect the table we created earlier and verify that there is a row with a session id, and the session content saved as bytes:

Notice, that the two fields which could store a timeout are empty. The session is valid indefinitely, which might not be the best way to handle sessions. The lifetime of our session cookie, which is still needed to store the session id on the browser side, however, is tied to the browser session. If we close our browser, open it again and visit http://localhost:80 again, our cookie is gone, we receive a new one and also create a new serverside session, because we can no longer attach the user to our existing session. This creates many new records in our table, which are never cleaned up, because we assume our serverside sessions live forever. We can configure this behavior with another ring middleware, the session-timeout middleware. jdbc-ring-session is configured to use the config parameters provided by session-timeout. Again, we need to add a new depencency to our boot.build file, [ring/ring-session-timeout "0.2.0"], and reference a function from it in our ns header of core.clj: [ring.middleware.session-timeout :refer [wrap-idle-session-timeout]. Then we wrap our handler in the new middleware. It requires two config parameters: :timeout, which defines the session timeout duration in seconds, and :timeout-response, which defines the response our server sends in case of a timeout. We could also switch :timeout-response with a timeout handler, more details about this can be looked up in the documentation. When wrapping the handler in several middlewares, I like to use the thread first macro to keep it readable. The main method now looks like this:

(defn -main

"Starts the web server and the application"

[& args]

(let [session-store (jdbc-store (:db env))

port (:port env)

session-expiry-in-minutes 5]

(run-jetty

(-> app-handler

(wrap-idle-session-timeout {:timeout (* session-expiry-in-minutes 60)

:timeout-response {:status 200

:body "Session timed out"}})

(wrap-defaults (-> site-defaults

(assoc-in [:session :store] session-store))))

{:port port})))

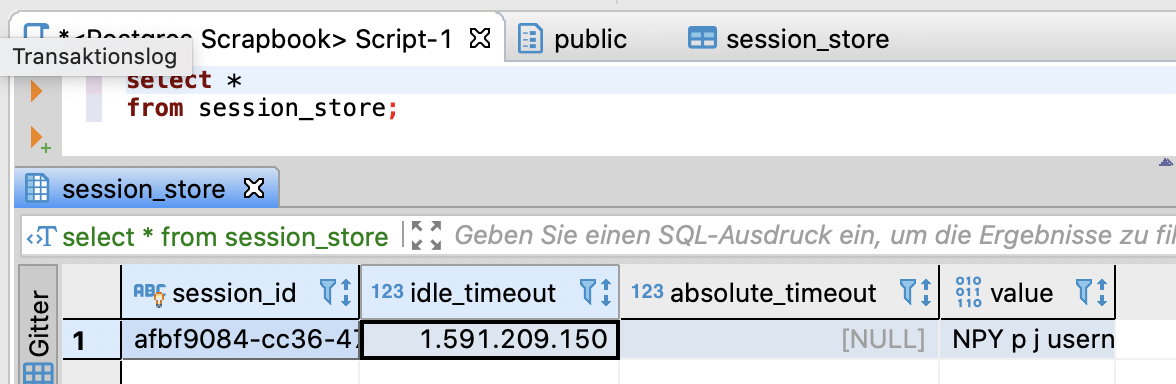

When we now clear our session table, start the application and visit its webpage again, a session timout value is included in the record:

Cleaning up stale sessions

Unfortunately, we are still not done, yet. The session timeout date is now stored in the database, but this doesn’t mean that the sessions will be cleaned automatically. But we won’t need another library, this time. The function to start a cleanup job is already included in jdbc-ring-session. We refer it in the header of core.clj: [jdbc-ring-session.cleaner :refer [start-cleaner]] and add it to our main function. It performs a cleanup run every 60 seconds by default, or can be configured with the parameter :interval. We restart the application, again, wait for some minutes and can see the session disappear from our database after it expired. This concludes part 3 of my Cloud Ready Clojure series, the code of our complete application is appended here in full - all 44 lines:

(ns scrapbook.core

(:require [ring.adapter.jetty :refer [run-jetty]]

[rum.core :refer [defc render-static-markup]]

[config.core :refer [env]]

[ring.middleware.defaults :refer [wrap-defaults site-defaults]]

[ring.middleware.session-timeout :refer [wrap-idle-session-timeout]]

[jdbc-ring-session.core :refer [jdbc-store]]

[jdbc-ring-session.cleaner :refer [start-cleaner]])

(:gen-class))

(defc html-frame []

[:html

[:head

[:title "A Scrapbook"]]

[:body

[:h1 {:id "main-headline"}

"Welcome to Scrapbook, Stranger!"]

[:div {:id "min-content"}

"We hope you will like it here"]]])

(defn app-handler [request]

(let [{session :session} request]

{:status 200

:headers {"Content-Type" "text/html"}

:body (render-static-markup (html-frame))

:session (assoc session :username "Tim")}))

(defn -main

"Starts the web server and the application"

[& args]

(let [db-conf (:db env)

session-store (jdbc-store db-conf)

port (:port env)

session-expiry-in-minutes 5]

(start-cleaner db-conf)

(run-jetty

(-> app-handler

(wrap-idle-session-timeout {:timeout (* session-expiry-in-minutes 60)

:timeout-response {:status 200

:body "Session timed out"}})

(wrap-defaults (-> site-defaults

(assoc-in [:session :store] session-store))))

{:port port})))

Until now, our application:

- Serves web content at port 80

- Renders a simple, serverside webpage

- Provides a HTTP web stack including cookies, security headers, content headers and session handling

- Stores the session in a PostgreSQL database

- Cleans stale sessions in intervals

- Can be configured differently for different environments

Prospect

We are already able to configure databases in different environments with the config library we are using - but if we deploy our application into a cloud environment with a fresh database, the startup will fail. The table we created in our local environment is not there, yet. In the upcoming part 4 of this blog series we will make sure that a delta database changes is adapted to every environment we will deploy to, so we don’t need to create tables by hand, or include SQL migrations into our pipeline.